|

|

|

|

|

| About | Photo Gallery | Hot Springs | All Shaheed | Activities | Contact Us |

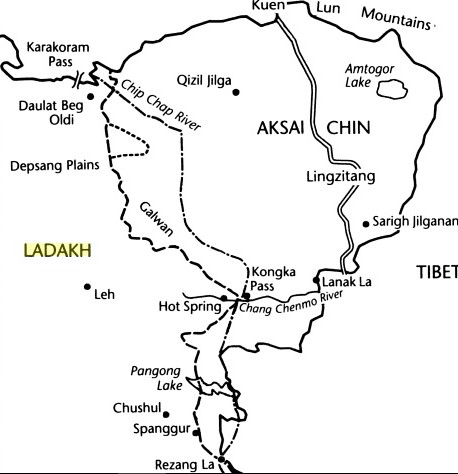

HOT SPRINGS LADAKH - THE PILGRIMAGE OF INDIAN POLICE FORCES   SINCE THEN OCT 21ST IS REMEMRED AS Police Commemoration Day ALL OVER INDIA. It was an event that changed the course of history in the subcontinent. It brought together the nation as few other things could. It opened up the floodgates and brought out an issue that many had tried to control from the public. And the events that precipitated in the years to follow finally culminated with the launch of the Chinese invasion on 20 October of 1962 and the worst defeat the Indian armed forces have ever faced. It was supposed to have been an outlet of frustration for some in the Indian Government, tired of the passive line Prime Minister Nehru had been taking with regard to the border dispute with China. Designed to exert a physical Indian presence in the mountainous regions of Laddakh, the process had started off miserably, and for the men involved, ended in tragedy. This is the story of those men involved at the pointed tip of what became the eloquent symbol of failed Indian foreign policy and strategic planning. Their story has a beginning back in the late 1950s. The Chinese had started, and completed, the construction of their strategic road through the traditional caravan route that passed from Sinkiang to Tibet through the Aksai Chin. It is common belief today that its construction had gone virtually unnoticed but the fact remained that several Indian Army reconnaissance parties as far back as 1952 (four years before the construction of the road began) had come across incriminating pieces of evidence that suggested the Chinese had such intentions in the region. One such patrol was conducted by Captain R. Nath, Captain Suri and a small detachment of soldiers from the Kumaon Regiment and the Laddakh Militia. This team went out from Leh in 1952 and headed through vastly barren mountainous terrain to reach a location called Hot Springs which was west of a critical mountain pass called Lanak La. It was here that they first came across reports from the locals that the Chinese were planning to build a road through the region and that Chinese engineers had been spotted conducting surveys in the region. Captain Nath and his team made it back safely to Leh and reported the Chinese intentions as well as the current lack of Chinese forces in the region. Despite the congratulations from the Ministry of Defense and Army Command, the team’s report was made secret and unfortunately, not acted upon. It should be noted that the team under Captain Nath and Captain Suri had reached Lanak La which lay at the traditional Laddakh-Tibet border and had encountered only scattered reports of Chinese engineers while no contact was made with any PLA unit. From this time in 1952 to around 1955 the PLA presence in the region was minimal. Had the Indian government acted during these years and placed troops in the Aksai chin before PLA units moved into the region in around 1955, the outcome of the border dispute could have been vastly different. But the Indian government was going through a phase of friendly relations with the Chinese that made major decision makers from Nehru downwards blind to the cunning strategic plan the Chinese were enacting for the world. The first warning signs of increasing Chinese presence in the region were the increased “bumping” of Indian and Chinese troops in the region, though no exchange of fire took place. New Delhi ignored these new pieces of evidence as well the old ones in the name of maintaining friendly relations with China. Later, in October 1959, at the Governor’s conference, General Thimayya said that in 1957, after the road had been completed, he had proposed military steps to counteract the Chinese move but had been grounded by Defense Minister Krishna Menon on the grounds that China was a friend and that Pakistan was the “main military danger”. The fact that the Army Command and the Ministry of Defense knew of the Chinese intentions to build a road as far back as in 1952 when no Chinese troops were in the region and chose not to act on it suggests that the Indian Army in addition to the Ministry of Defense was not entirely free of guilt for the events that were to follow in the Aksai Chin. By 1957, the Chinese were in firm control of the Aksai Chin and faced only scattered Indian Armed police outposts in the region east of Leh. By this time the Chinese were certain of their position that an official announcement in Peiping was made on 2ND September 1957 that the Aksai Chin road was to be completed in October of the same year. The announcement came forth in the People’s Daily which also presented a map of the region showing the Aksai Chin as Chinese territory.

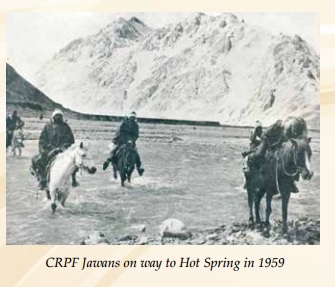

The situation could now no longer be ignored in New-Delhi, but the strategic window to create an unopposed military presence in the region had now passed years ago.This was made clear to the Indians when one of the two reconnaissance patrols sent out in June 1958 to determine Chinese presence in the Aksai Chin, was captured by the Chinese in September of the same year as they neared the road. The treatment of the Indian prisoners was not proper. The patrol leader was in fact placed in solitary confinement during his interrogation before all of them were released. It reflects the complete fantasy that the Indian leaders had created around themselves regarding the military situation at the border that Prime Minister Nehru had personally ordered the men of these patrols to secure Chinese prisoners and detain them for questioning back in Leh or in case of a larger force, to “ask them to leave.” By late 1958, it was impossible for the Indian Army to be able to send a patrol all the way to the Lanak La without getting stopped and detained by the Chinese along the way. The PLA had not only moved into the Aksai Chin, they had secured vast regions of the plain west of where their strategic Sinkiang-Tibet road cut across the region. Further westward movements of troops were discovered when Chinese troops were detected as far west as Khunark Fort and Pangong Lake in the south. It is worthwhile to notice that such incidents were not publicly known at the time. Prime Minister Nehru’s aides have since reported his anxiety to maintain such a restriction on the release of such information to the public. The government also ensured that the information given out by the released members of the patrol that had been captured in 1958 regarding their treatment was not released to the public. The notes of exchange between Nehru and Chou also suggest that the Chinese leaders were just as pleased with such a restriction on release of information as Nehru, but for entirely different intentions altogether, though it is uncertain whether at that time Nehru knew their motives. As a result, as far as the Indian public was concerned, the Sino-Indian relations were going though a rough patch but nothing more. By summer of 1959 however, following the Tibetan revolt and the flight of the Dalai Lama to India, the moods had changed remarkably within different sections of the Indian government. Several crucial events happened in the summer of 1959 that was to set the stage for the later years. Prime Minister Nehru for one had finally begun to realize that the Chinese had been exploiting his genuine feeling of friendship with them . But his response was to ensure that further deterioration in the Sino-Indian relations did not take place. To this effect Indian officials were under strict instructions not to antagonize the Chinese . By September 1959, the ITBF forces in the region were coming under increased pressure from the Chinese forces at the border. In early September a patrol party of Indian soldiers was captured east of Chushul by the Chinese and released in the beginning of October near Chushul airbase. It was during this time of their being held prisoner that one ITBF officer, DSP Karam Singh, got orders from the Deputy Director of the Ministry of Home Affairs on 22ND September to establish new posts right at the Chinese occupation line in Laddakh. His first outpost was supposed to be at a place called Hot Springs. It was therefore that a full seven years after Captain R. Nath and Captain Suri had travelled through the same terrain and gone past Hot Springs all the way to Lanak La that the Indian Government ordered the deployment of lightly armed police forces to defend the border from a vastly experienced and battle hardened enemy army. This decision requires some scrutiny. It is worthwhile to remember that by this time there was sufficient evidence that heavily armed Chinese forces were deployed deep inside Indian Territory in Laddakh. The answer to the question as to why the Indian government chose to forward deploy lightly armed police units on shoestring logistical support to face this massive military force rather than Indian Army units brings out some bitter realities. The fact of the matter was that by this time in the dispute the Chinese were too far down the line in terms of deployment for the Indians to even begin to think about catching up. The nearest Army Garrison was at Leh. The only units available for the Indian Government to use to project force quickly were the ITBF and the CRPF units. But even then the picture is not complete. It needs to be mentioned that back on 13TH September, mere days after the capture of the Indian policemen near Chushul, Prime Minister Nehru had prohibited all forward patrolling in the Laddakh sector.  And yet DSP Karam Singh had received orders to head east from Leh and prepare a line of new posts right opposite the Chinese forces. For all intents and purposes the jurisdiction of the operation was given to the ITBF units under DSP Karam Singh and a force of forty CRPF personnel deputed to the ITBF under DSP S.P. Tyagi. A few days after the release of the captured policemen near Chushul Airstrip in early October, this combined force of men, some sixty strong, moved out east from Leh on a week long trip through the high mountains on foot. Eventually they arrived at their destination at Hot Springs on 19TH October, a few kilometers west of the first known Chinese positions and established a temporary camp there. Hot Springs in ladakh is situated between 15,000 and 16,000 ft above the sea level For DSP karam Singh and his companyat the western front not only have to confront the intruding Chinese forces, but also have to fight against the worst natural environment and to overcome tremendous difficulties imposed by pleatu's frigid climate and lack of oxygen. The moutains are snow covered throughtout the year. The climate undergoes great variations;like violent snowstorms and at times sand storms accompained by rolling pebbles. Due to lack of oxygen, execution of the tasks like, building defense works, setting up posts and even walking was most difficult.Sometimes, because of the strong winds in the passes, there was no way to set up tents, the policemen had to dig snow caves and pits to hold fast to posts. Because of lack of oxygen, the boiling point of water was just 50-60 degrees celsius,making it difficult to cook food. men had to survive on frozen canned food and drink water from snow.Some newly built posts had only a single tent with no heating equipment and fuel. During night,the policemen had to keep themselves warm by huddling togather. On the morning of the 20TH, Karam Singh ordered a small reconnaissance party consisting of two constables and a porter to head east and report back on Chinese activities a few kilometers away. He intended to get an idea of the Chinese deployments in the region before attempting to move north and establish the first of the posts in the region. A common time was set up for this patrol to return. However, by late evening on the 20TH, there was still no sign of the two constables or the porter. Fearing that the small reconnaissance team might have lost their way, Karam Singh sent out a larger team of ten policemen to go out and look for the three lost men. This search party returned at 2300 hours that same night without being able to find of the three man patrol. They did, however, after travelling some ten kilometers, discover hoof-prints on the ground suggesting that the Chinese soldiers had been in the region. At 7am the next morning, the 21st of October 1959, Karam Singh and Tyagi led a team of around twenty policemen armed with bolt action rifles in search of the missing policemen and they left camp on ponies. The rest of the force was ordered to follow behind on foot. Karam Singh and his advance party reached the same region as the team the previous night had done and again found the hoof-prints. This time, however, Karam Singh, Tyagi and their small team dismounted and awaited the arrival of the main force. When the main party did arrive, it was decided that Tyagi would stay behind and command this larger force while Karam Singh and his small group of twenty would follow the tracks and see if they led to the Chinese intruders in that sector. It was at this point that the main force and the smaller advance team under Karam Singh lost sight of each other as a result of the hill feature along the bank of the Chang Chenmo River where the hoof-prints continued. Suddenly a Chinese officer was spotted on this hill overlooking both the teams as he waved to Karam singh to raise their hands and surrender. The Chinese had ambushed the entire force of Indian policemen. Now the Chinese were at an elevated position in fortified bunkers and trenches and armed with mortars and heavy machineguns looking down on an exposed Indian police force. But the brave Indian policemen were not ruffled by this show of force. Karam Singh lifted a handful of mitti(mud or soil) from the ground below where he stood to gesture to the Chinese officer that this was Indian soil. Apparently the Chinese officer did the same. Such back and forth gestures went on for three hours after which the Chinese officer disappeared from view a moment before a boulder rolled down from one of the Chinese bunkers higher up on the hill. A few seconds later there was a volley of fire from the hill above forcing the Indian policemen below to scramble for cover. Moments later Chinese positions on a nearby hill, so far undiscovered, also opened fire and caught the Indian troops in crossfire. Chinese heavy machineguns joined the fray as they poured fire on the beleaguered Indian policemen on the river bank below. Karam Singh’s men, armed with mere bolt action rifles, could not hope to survive this onslaught and it wasn’t long before his men started taking casualties. One of the members of his twenty force team, a constable named Ali Raza, managed to escape from the Chinese gunfire and run back and report to the main group under Tyagi as to what was happening. But Tyagi’s force was also under heavy attack and was pinned down. It was a massacre. Ten CRPF men in Karam Singh’s remaining force of nineteen were killed by evening while most others suffered some form of injury or another. One of the constables, Makhan Lal, was seriously injured by a bullet in the stomach. Faced with complete decimation of his men under the relentless Chinese gunfire, Karam Singh finally surrendered along with his nine wounded survivors later in the evening. The main force under Tyagi was forced to retreat and their attempts to recover the bodies of the dead CRPF men later in the night was in vain since many of the forty men under his command had also been wounded to some degree or another and the Chinese still dominated the hill above the riverbank which they continued to hold even on the 22nd October when Tyagi was finally ordered to retrieve his remaining force back to Tsogstsalu. Four of the more seriously injured policemen under Tyagi were airlifted to Srinagar on November 1st, 1959 to be placed in a Military Hospital there. For Karam Singh and the other Chinese prisoners the tragedy had just begun. The following excerpts are taken directly from a description given by Karam Singh himself after being released : “Five of us were made to carry the dead body of the Chinese soldier who had been killed. Constable Rudra Man and I were asked to help Makhan Lal, who had been injured seriously in the abdomen. We carried him for two miles where the Chinese ordered us to leave him on the bank of the Chang Chenmo River. From this place I and Constable Rudra Man were made to carry heavy loads. We were completely exhausted and were finding it difficult to walk with this heavy load but we were repeatedly prodded by rifle butts to move on. “We reached the Chinese Kongka La post (above 16000 feet) at about 2 AM on the 22nd of October 1959. We were all put together in a pit six feet deep, seven feet wide and fifteen feet long, normally used for storing vegetables. It was covered with a tarpaulin which left several openings through which the ice-cold breezes penetrated. We had to spend the night on the frozen ground without any covering. No water for drinking was provided nor were we permitted to ease ourselves during the night and the following day. For the first three or four days we were given only dry bread to eat. The intensity of the cold and our conditions of living were more than sufficient torture to demoralize us. By then I and three constables were suffering from frostbite and our repeated requests for medical attention and hot water were disregarded.” Fresh snow was falling over the region on the 24th October when Karam Singh was shown the corpses of the Indian policemen killed during the gunfire and asked to indentify them. Then for the next twelve days he was tortured along with the others to make him admit that the Indians had opened fire and precipitated the skirmish: “At first they asked me to narrate the entire incident. As soon as I came to the point that the firing was opened by the Chinese, their senior officer present became wild and shouted back that it was incorrect and that I must confess that the Indians fired first. I refused to accept this despite repeated and constant threats that I would be shot dead. Ultimately they made me say that I could not judge at the time as to who fired first.” The Chinese also tried to make Karam Singh and the others admit that they had known before the incident that they had intruded into Chinese territory. Unable to get such a confession, the Chinese forged the statement attributed to Karam Singh to the effect that “I have now come to know that the area where the encounter had taken place is now under Chinese occupation.” Karam Singh reported that during his interrogation the Chinese attempted to make him confess that the Chinese officer who had made himself seen just before the incident had tried to warn them to leave. The basic idea behind all of this was of course to show that the Indians were the ones who had caused the incident and not the Chinese. The interrogation technique was extremely brutal: “This interrogation lasted from 4:00 AM to about 4:00 PM. By this time I was frozen and mentally and physically exhausted because of cold, persistent interrogation, intimidation, threats, angry shouting and lack of sleep. In this condition I was compelled to sign the statement recorded by the Chinese. At the end of this interrogation the Chinese then brought all the other captured personnel before me and read out the statement and several photographs were taken.” The interrogation continued on the 27th and 28th when the Chinese extracted ORBAT information concerning the Indian border deployments. On the 28th all of the Indian policemen were taken to the bank of the Chang Chenmo River where photographs were taken by their captors as they washed the bodies of the dead comrades in accordance with custom. Photos were also taken of the prisoners being issued with warm clothing, padded in Chinese style . On the 29th Karam Singh and the others were taken to the original battle scene and forced to re-enact the events which had taken place. The incident was staged according to the Chinese version of the events while photographs were taken as evidence. On November 7th 1959, an indoctrination lecture was delivered to the Indian prisoners while they were made to sit in the bitter cold of the Karakoram mountains.

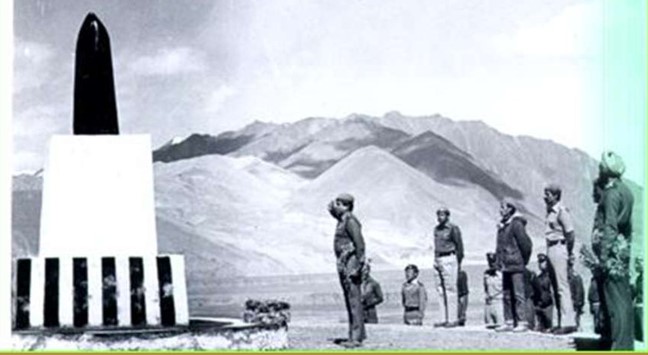

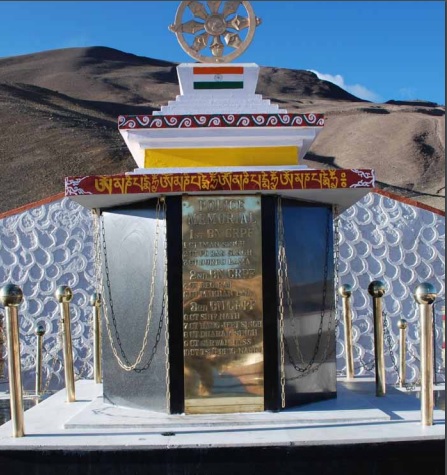

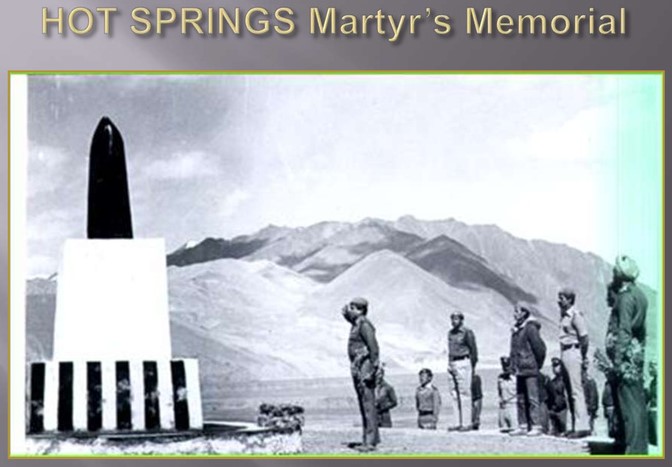

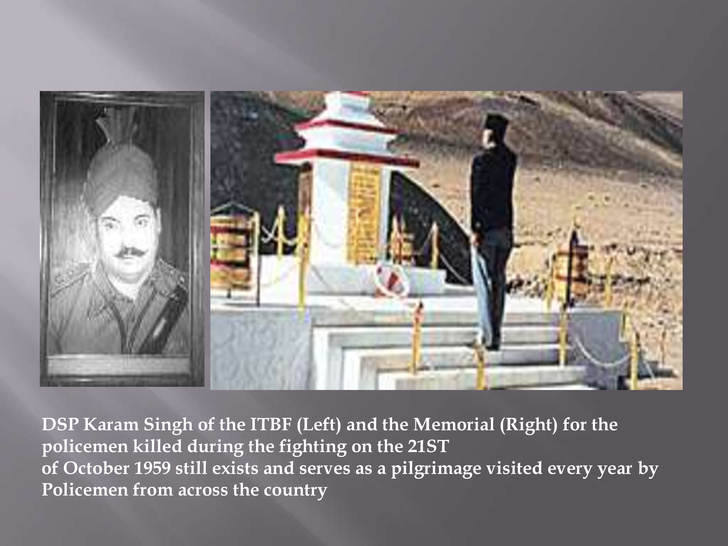

DSP Karam Singh of the ITBF (Left) and the Memorial (Right) for the policemen killed during the fighting on the 21ST of October 1959 still exists and serves as a pilgrimage visited every year by Policemen from across the country 6 On November 14th 1959, Prime Minister Nehru’s birthday, the Chinese returned the three Indian policemen captured on October 20th along with Karam Singh and the rest of his surviving men. The bodies of the ten brave CRPF men were returned by the Chinese at the Indo-China border on November 13TH 1959. The body of Constable Makhan Lal was never returned and remained unacknowledged by the Chinese. The last time he was seen was where the Chinese had forced Karam Singh and his men to leave his wounded body on the bank of the Chang Chenmo River under the protection of Chinese soldiers. He was most likely neglected and died of his wounds but there are no confirmations of this ruthless act on the part of the Chinese. In a final act of humiliation, the Chinese allowed only ten Indian policemen to approach the actual Indo- China border. These ten men had to bring the bodies on horseback all the way back to Hot Springs. One of the constables of the ITBF who went along to collect the bodies was Sonam Wangyal, who had been in Tyagi’s main force during the original encounter on the 21st of October. He recollects the grim transfer ceremony :  Sonam Wangyal “Even while we were collecting the bodies, Chinese women in uniform were clicking photographs. The Chinese soldiers were wrapped in snow-white warm clothing and snow-boots while were in out woolen Angora shirts and jerseys, bearing the brunt of the biting cold at that prohibitive height of 16,300 feet.” Events in the outside world The day after Karam Singh and his group of survivors surrendered under the overwhelming Chinese fire, news of the incident began to filter out all the way to New-Delhi. On 23rd of October the Ministry of External Affairs submitted a note to the Chinese Ambassador in Delhi. This note represented the first official protest to the incident from the Indian Government. However, on the inside, Prime Minister Nehru and the Army Commanders had immediately come to realize that something else had happened. “On October 23rd, when the facts of the outrage came to be known, the Prime Minister held a meeting which was attended by the Defense Minister, the Chief of Army Staff and officers from the Ministry of External Affairs, Home and Defense. The Intelligence Bureau was made the common target by the Army Headquarters and the External Affairs Ministry and accused of expansionism and causing provocations at the frontier. The Army demanded no further movements of armed police should take place on the frontier without their clearance and the Prime Minister had to give in to the Army’s demand. The result was that protection of the frontier was thereafter handed over to the Army and all operations of the armed police were made subject to prior approval of the Army Command. On the 25TH, the Indian outposts in the region began receiving reinforcements and medical supplies as New-Delhi attempted to recover from the shock it had received. On the 27TH, the Chinese Foreign Ministry informed India and the world that it was prepared to release the captured Indian policemen “at any time”. The report also declared for the first time that India’s account of the facts had been “inconsistent with the facts and contrary to the truth”. It also rejected India’s claim for compensation for the families of the dead Indian policemen, adding that “if the question of compensation is to be raised, it is only the Chinese side, and not the Indian side, that has the right to make such a claim” . It was around this time that Karam Singh and the other Indian policemen were being tortured to extract the statements that they had intruded into Chinese territory. Consistent with this fact, the first Chinese claims that India had provoked the incident began to surface in various Chinese state media. On November 1ST, 1959, the Indian Army took over direct command of the frontier with China, relieving the ITBF and CRPF forces in the region in this role. The Indian Army announced that a chain of outposts would now be built and troops would be placed there. This was in effect the beginning of what was later to become the notorious ‘Forward Policy’. The Chinese declared in a threatening note that should Indian Army enter Laddakh, it would make a “fresh entry” south of the MacMahon line. The importance of this statement cannot be understated for any future war with china. Indeed, it was a culmination of this statement that was brought about by the Forward Policy in the next few years that led to the Chinese attack on 20th October 1962. It was the Kongka La incident that brought the Indian public finally into the picture. There were mass protests on the streets asking for the dismissal of Krishna Menon as Defense Minister as also denouncing the Chinese. The Kongka La incident was already causing tempers to flare in India but in the coming days when Karam Singh and his men would be released, and their story would finally pour out, the effect would boil over. It was one of the most crucial events leading up to the 1962 war. The Hindustan Times wrote: “Inaction now can make war inevitable” while the Indian Express had a statement about Nehru that he had “sadly underestimated the real menace of Han expansionism and Communist Imperialism.” Public display of anger as protestors burn a copy of China Today in New Delhi after the 21 October incident while others demand the resignation of Defense Minister Krishna Menon in response to the loss of Indian lives in Laddakh Nehru however, was under no illusion regarding the imbalance of the armed forces of India and China when he discussed the incident at a public forum on the 25TH of October 1959, just days after the event. He temporized during the discussion and warned against rash action such as counterattacks etc being demanded by others. Other called on him to reject the non-alignment policy and join the west against the threat of communism as also to allow a significant buildup of military strength with help from the US and UK. Nehru flat out denied the abandoning of the non-alignment policy and reaffirmed this stand on a 1ST November public forum meeting. Instead he was quoted as saying that India would defend herself “with all her might”, although most members of the Indian Military took this with a grain of salt faced as they were with harsh realities of the situation at 16000 feet. Nehru also attempted to explain to the Indian public why the border in Laddakh had not been defended with more forces with a feeble (yet infamous) response: “We thought that the Chinese would not resort to force in the Laddakh area…” The mortal remains of the martyrs were returned by the chinese army on Nov 13, 1959

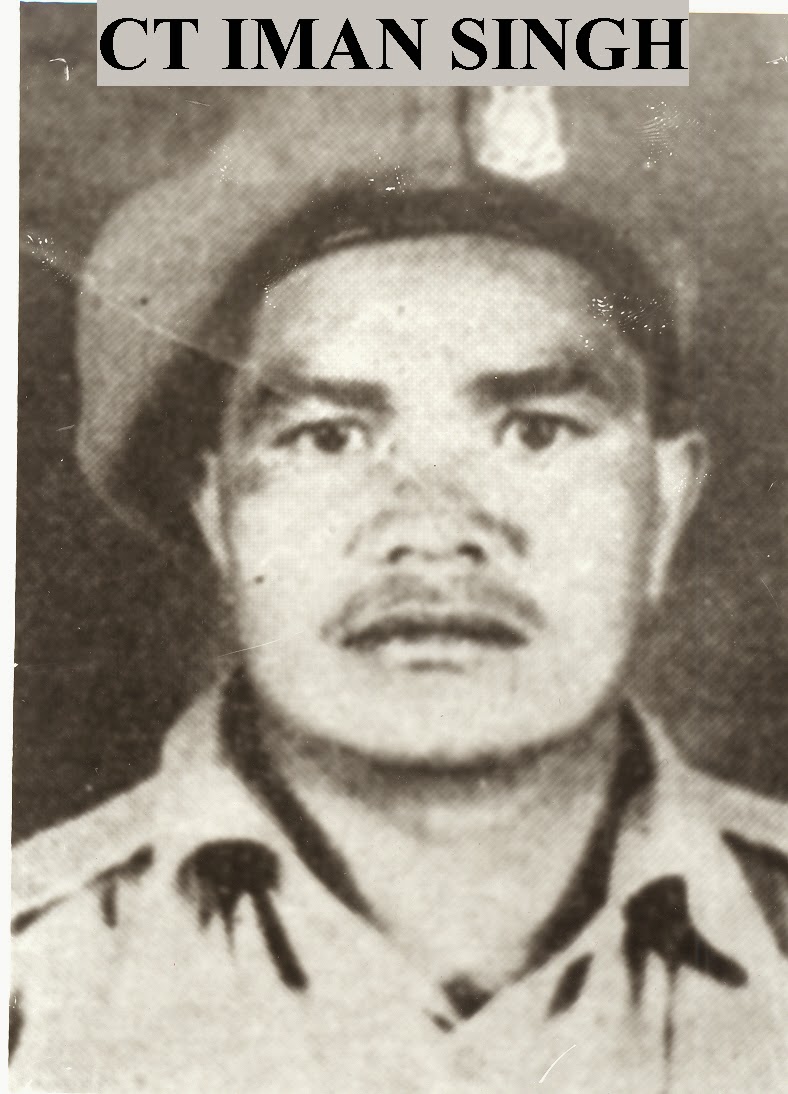

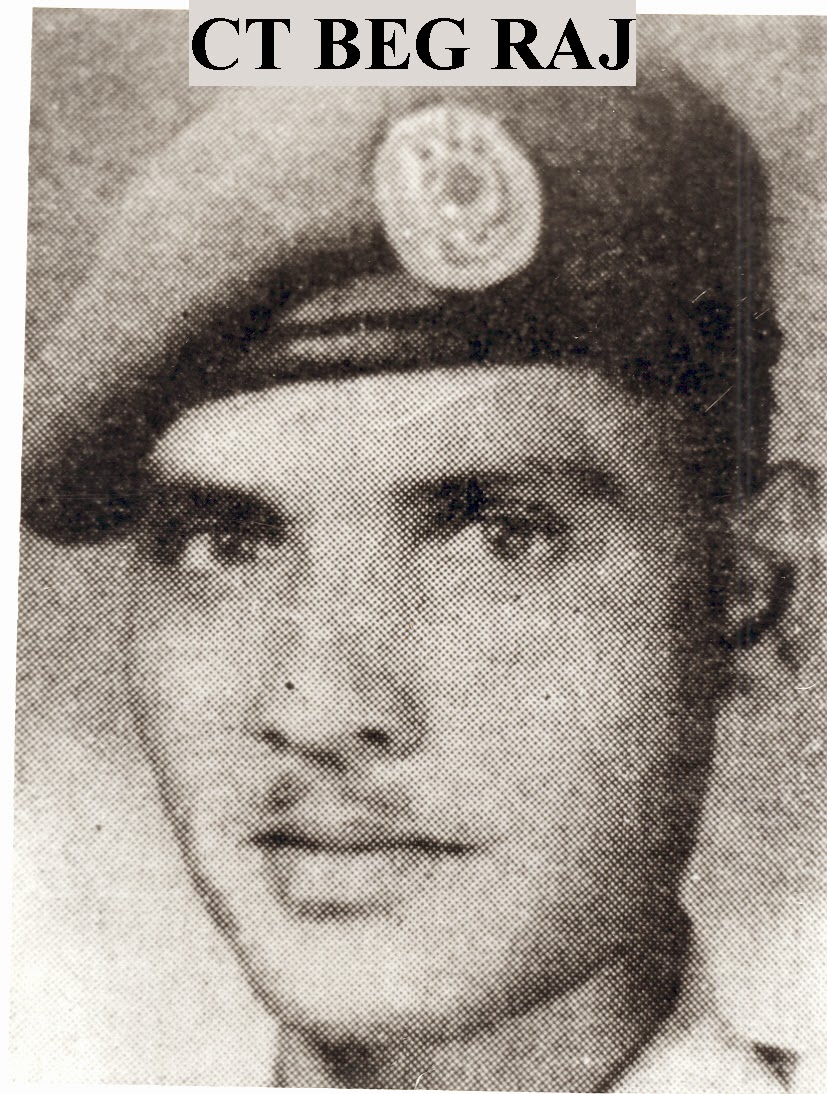

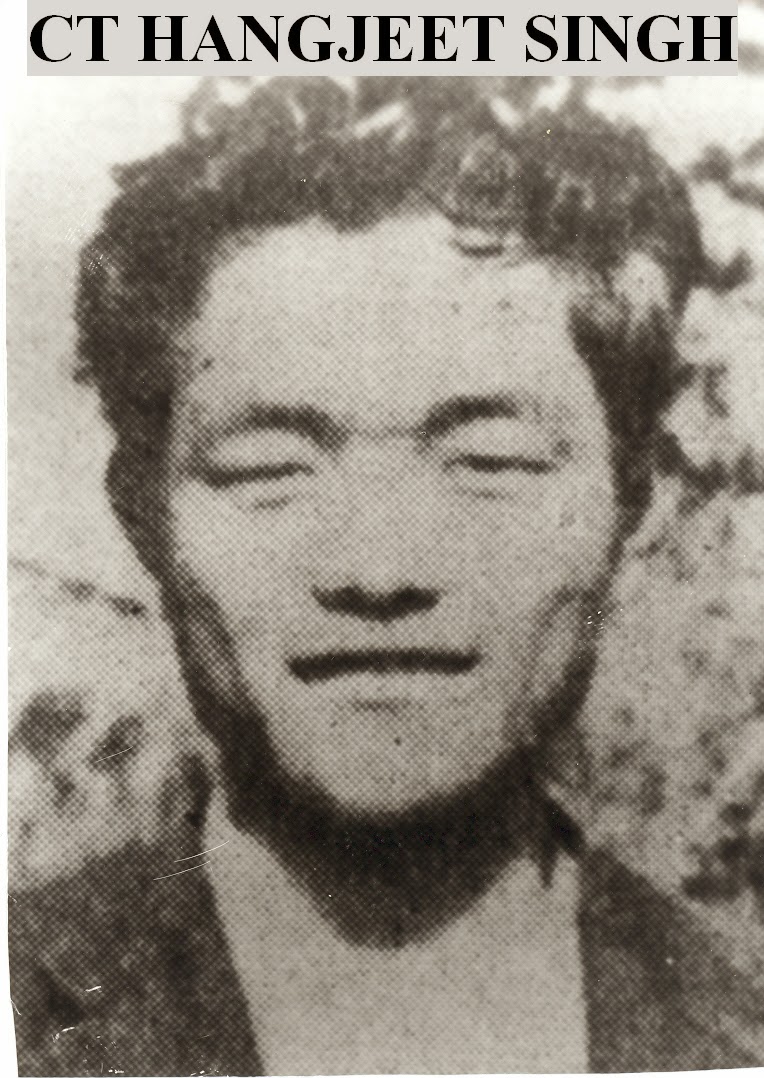

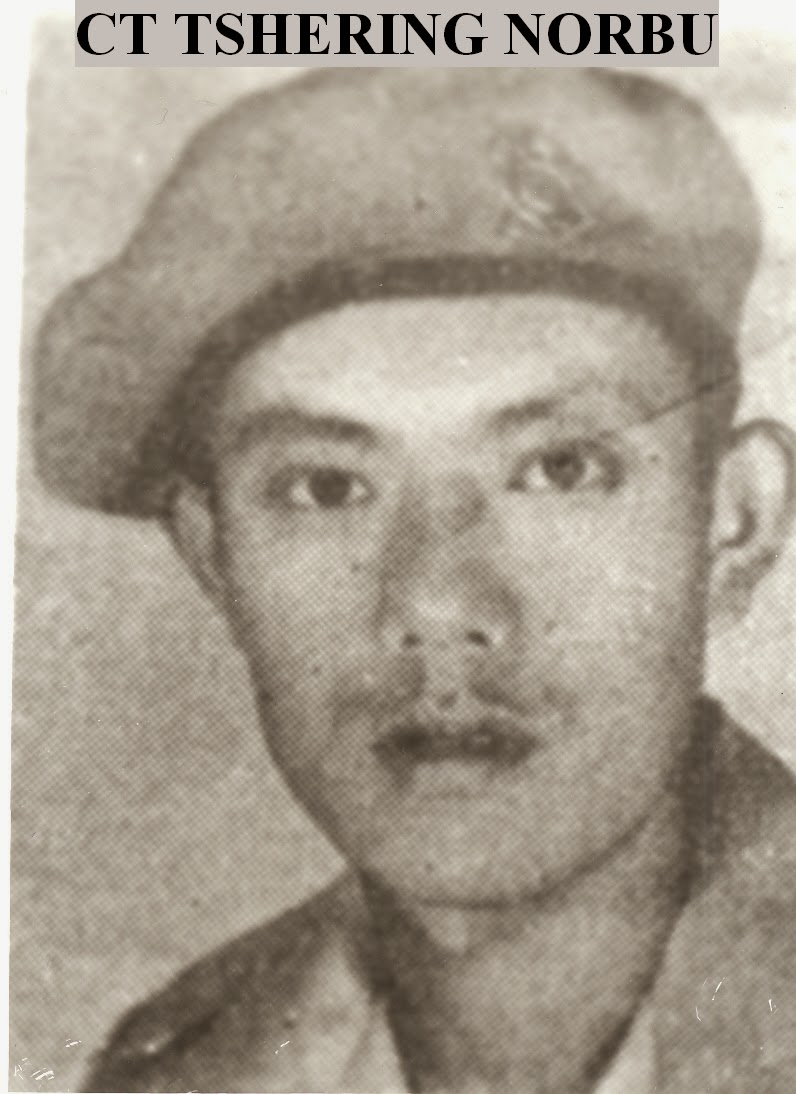

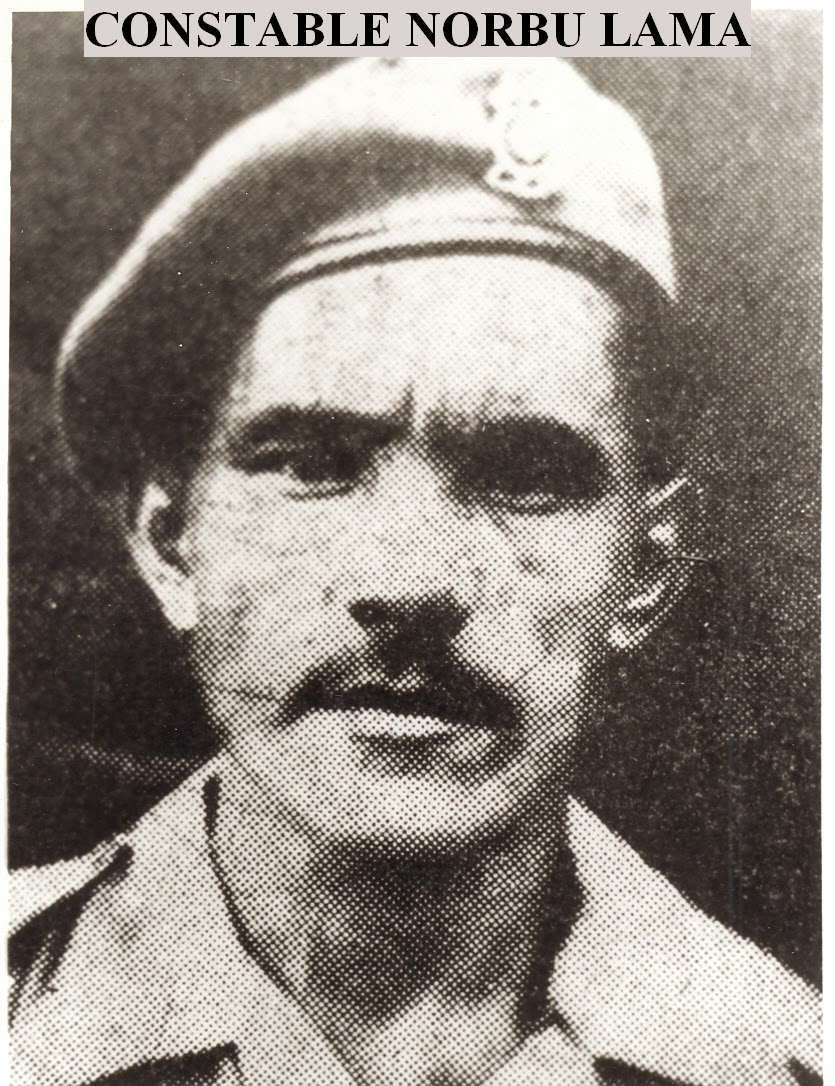

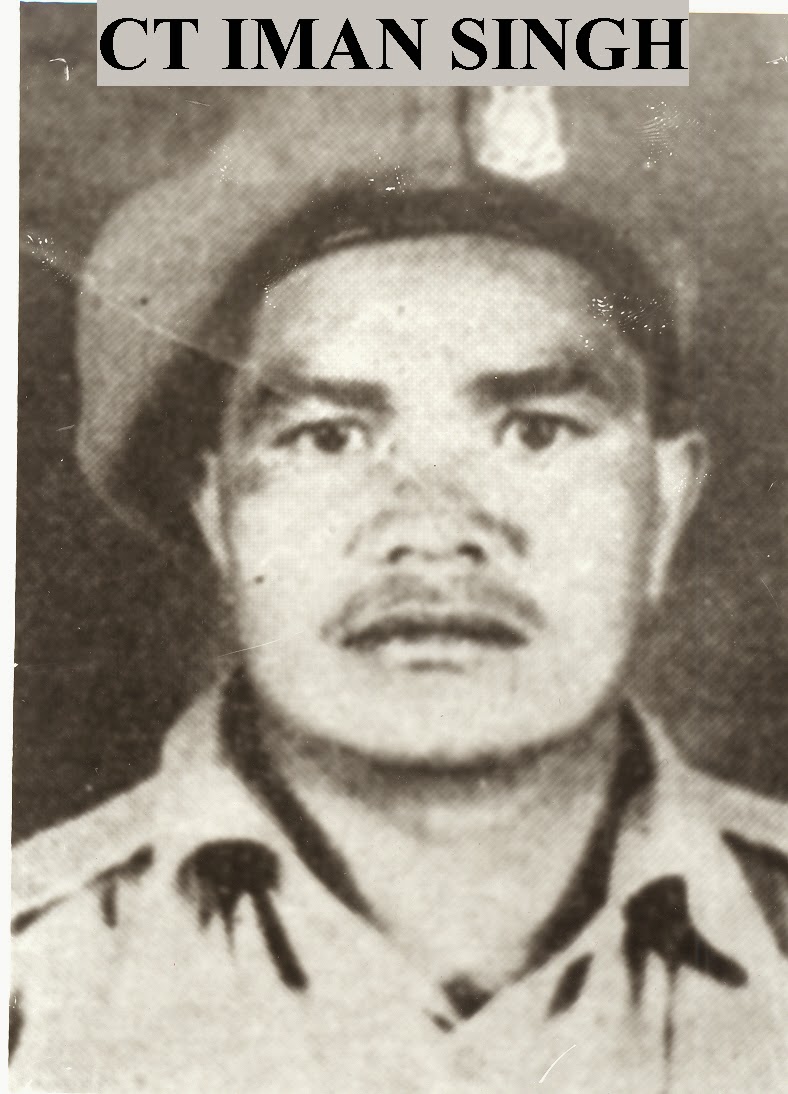

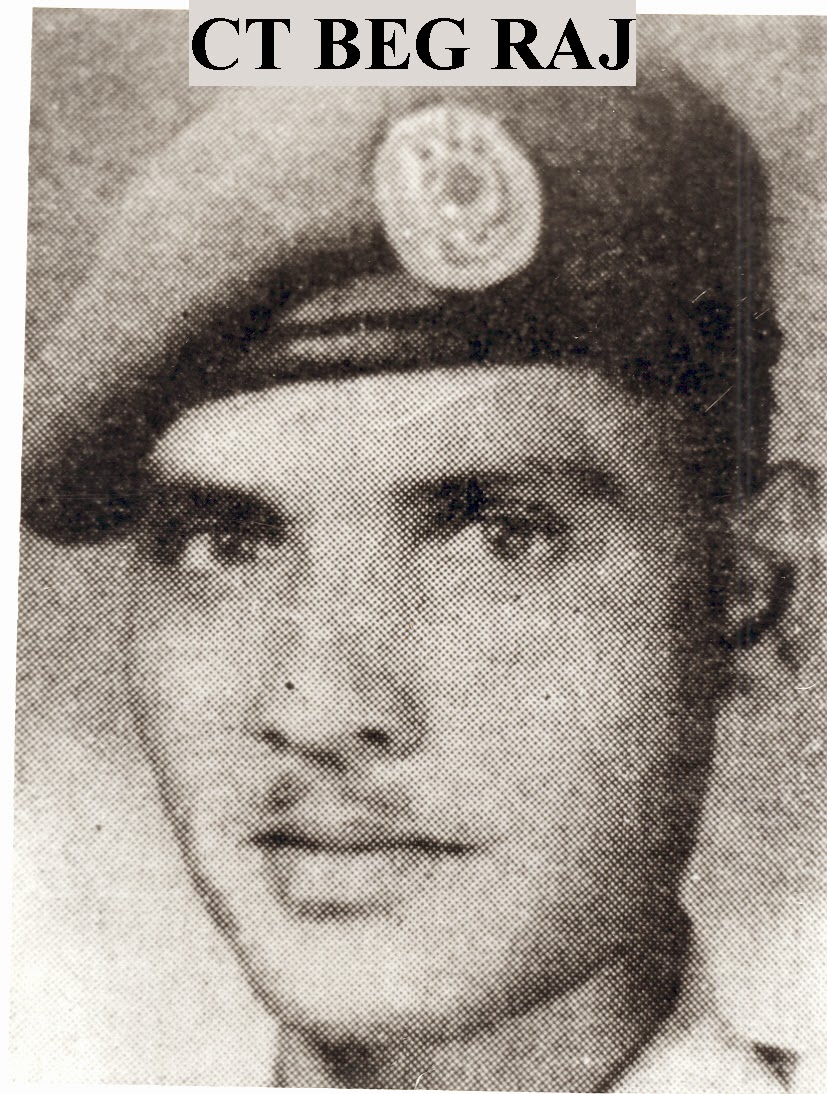

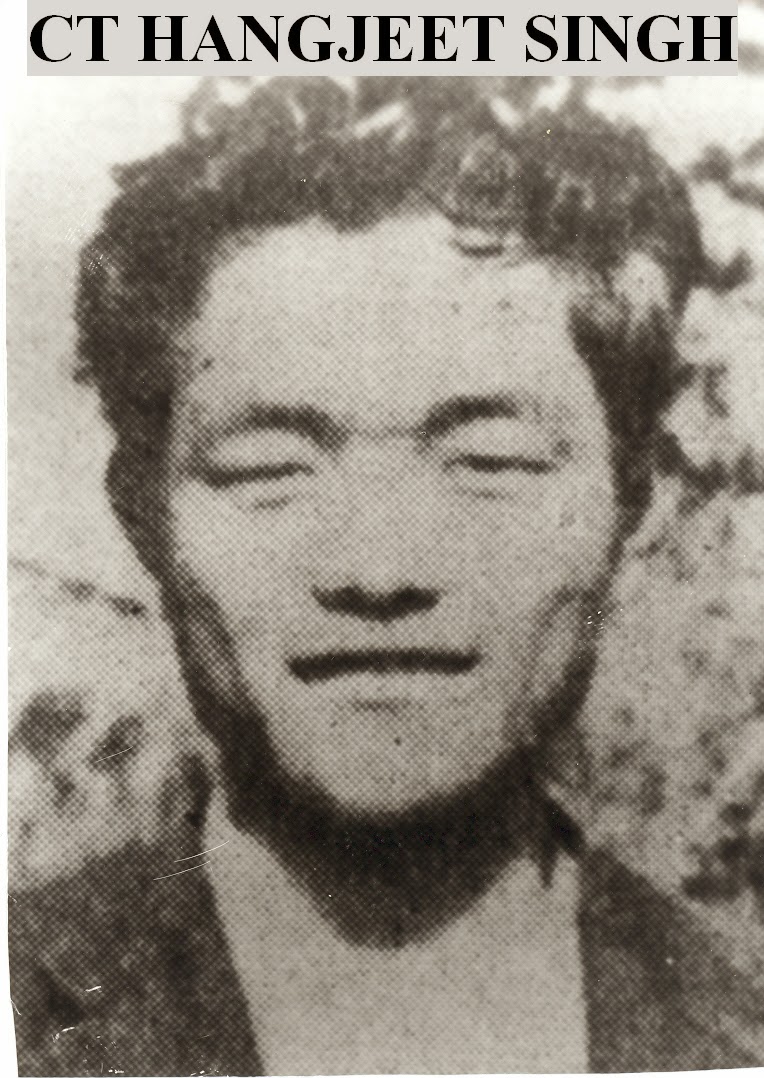

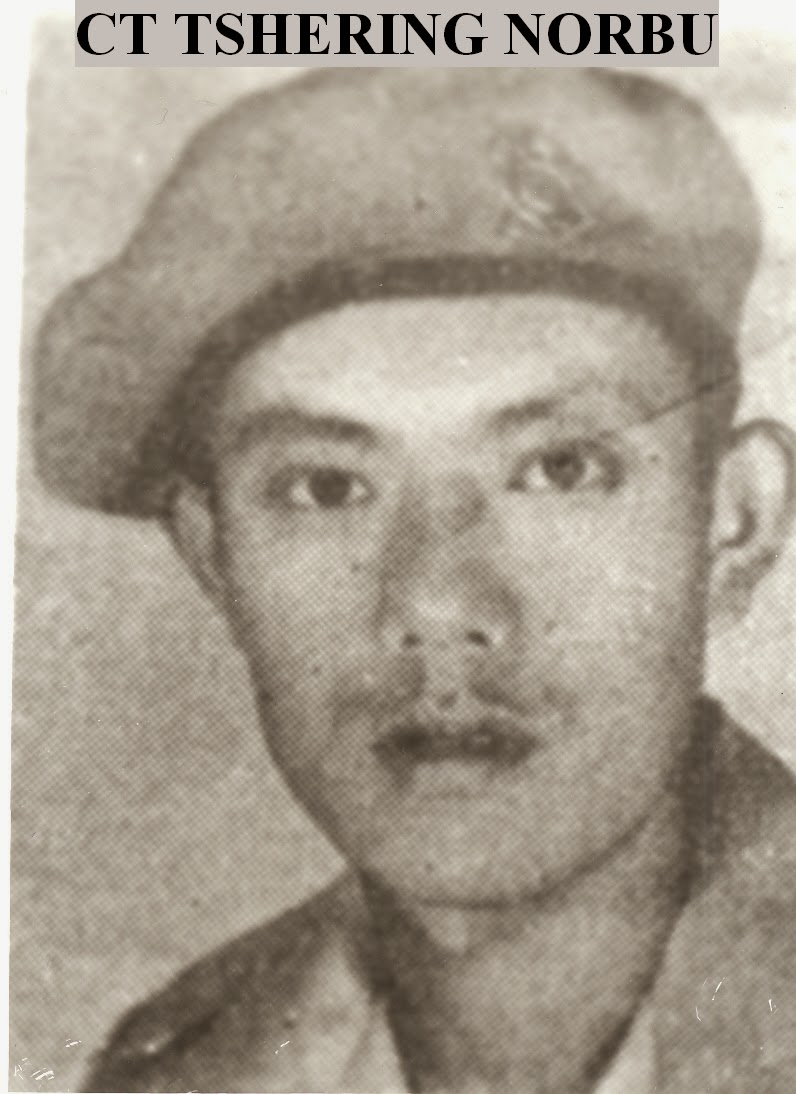

The names of ten gallant martyred men of CRPF are :

And at 8:00 AM on November 14th 1959, the bodies of the CRPF men were laid to rest with full police honors at Hot Springs in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir. Since 1961, the spot is a place of pilgrimage for policemen from all over the country who pay homage to the martyrs there. Karam Singh received a national hero’s welcome. He was awarded the President’s Police Medal by Prime Minister Nehru himself. Since then October 21st is remembered as the Police Commemoration Day all over India. It is a fitting tribute to those brave men who laid down their lives in defense of the country and their comrades who suffered under extraordinary conditions at the hands of the Communist Chinese soldiers almost fifty six years ago. The Annual Conference of Inspectors General of Police of States and Union Territories held in January 1960 decided that October 21 would, henceforth, be observed as Commemoration Day in all Police Lines throughout India to mark the memory of these gallant men who were killed in Ladakh and all other police personnel killed on duty during the year. It was also decided to erect a memorial at Hot Springs. Every year, members of police forces from different parts of the country trek to Hot Springs to pay homage to those gallant martyrs. |